Secret Agent for the Crown

Based on a presentation made to the Hamilton Branch on United Empire Loyalists’ Day, June 18, 2022

See also, for more detail, Samuel Wells of Brattleboro: The Life of a Loyalist in Vermont, base on a presentation made to the Hamilton Branch on February 27, 2024 and the Governor Simcoe Branch on March 6, 2024.

This is the story of how Samuel Wells of Brattleboro, Vermont served and suffered for the Crown during the American Revolutionary War, and how his children — more than fifteen years later — were rewarded for that service and suffering.

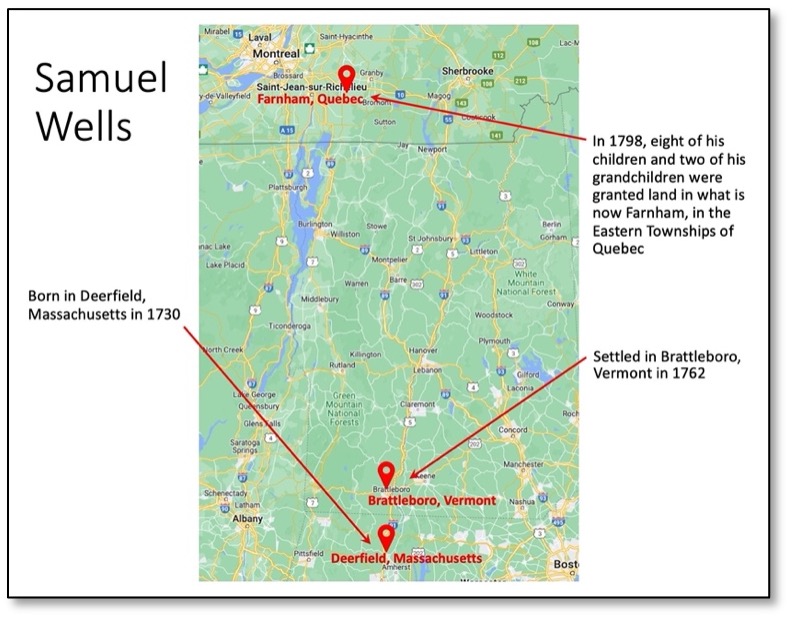

Samuel was the son of Jonathan Wells and his wife, Mary Hoyt, of Deerfield, Massachusetts. He was born in Deerfield on September 9, 1730 and married Hannah Sheldon there in 1751.

Deerfield is in the extreme north of Massachusetts, only a short distance south of what is now the Vermont state line. When Samuel decided to settle in Brattleboro in 1762, it was a journey of just twenty-five miles.

Samuel would die in Brattleboro on August 6, 1786, three years after the end of the war.

Fifteen years later, in 1798, a proclamation of the government of Lower Canada created the township of Farnham and granted about 14,000 acres of it to eight of Samuel’s children and two of his grandchildren.

Farnham is in the region known as the “Eastern Townships.” It’s within the ancestral territory of the Mohawk nation and about midway between Montreal and Sherbrooke. It’s about thirty kilometres north of the US border and, In 1798, it was virgin forest.

Over the next four years, from 1798 to 1802, most of the Wells family would settle there.

I should clarify one point. When I said that eight of Samuel’s children received land grants, that wasn’t strictly true. In fact, it was four of his sons and four of his sons-in-law. It seems the law, in those days, didn’t permit Samuel’s married daughters to own land in their own name.

So what had Samuel done, twenty years earlier, to earn his children such largesse from the Crown?

For that, we need to back up and take a moment to understand what Vermont was like before and during the war. Importantly, Vermont was NOT one of the thirteen colonies. It was a remote, sparsely settled, and disputed territory that was, until 1764, claimed by the colonies of New Hampshire on the east and New York on the west. When the Crown ruled, in 1764, that it belonged to New York, conflict arose between new settlers from New York and earlier settlers whose land grants had been issued by New Hampshire.

In 1777, residents declared the territory to be an independent republic, free of the Crown and free of New York. They called it New Connecticut but soon renamed it to “Vermont” (derived from the French for “Green Mountains”).

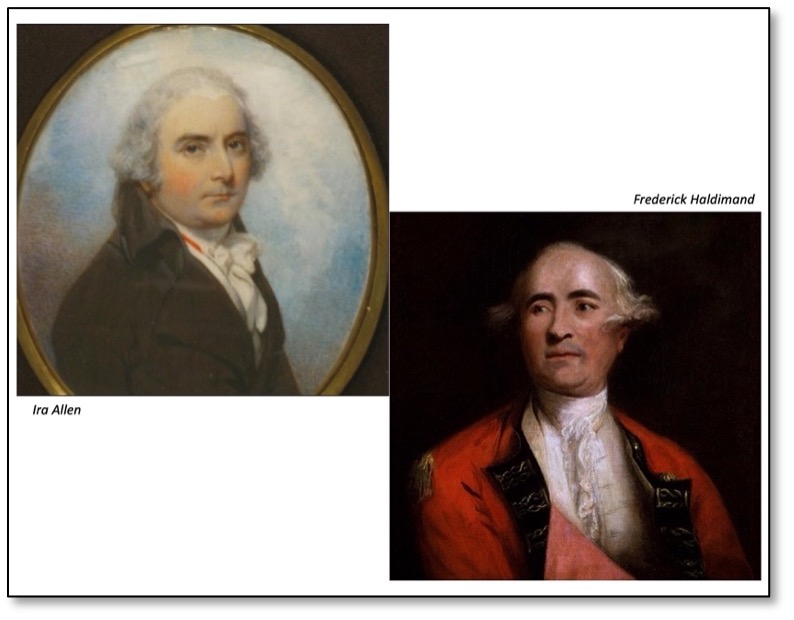

This new Vermont Republic aligned itself with the rebelling colonies, but its independent status seems to have given some of its leading figures room to play both sides, as the war ground on. In 1781, two of Vermont’s founding fathers, the brothers Ira and Ethan Allen, who had led the famous “Green Mountain Boys” militia, agreed to begin negotiations with the Governor of Lower Canada, Frederick Haldimand.

If successful, these negotiations would have given Vermont the same status, within the Empire, as Upper or Lower Canada. Imagine! Had the negotiations succeeded, Canada would now have eleven provinces, with Vermont as the eleventh.

That’s Ira Allen, one of the brothers, in the upper left, and Frederick Haldimand, in the lower right. And yes, this is the man that Haldimand county is named after.

Samuel Wells’s wartime service to the Crown was at least partially in furtherance of these negotiations.

It was only because he was one of Brattleboro’s most prominent and respected citizens, that Samuel was able to maintain his freedom and his life, while openly being a Loyalist and secretly working to advance the interests of the Crown.

One of my sources says that …

The condition of Colonel Wells [that is, his social and financial condition] was […] superior to that of most of the early settlers of Vermont, and the influence of his character and position was for many years extensively acknowledged.

By the time the war came, Samuel had lived in Brattleboro, on his 600-acre farm, for fifteen years. He was said to have been the “principal officer” of the local militia, where he earned the rank of Colonel. He had been a Justice of the Peace and a judge of what was called the “Court of Common Pleas.” In 1772, he had been elected as one of Vermont’s two representatives in the New York General Assembly.

Early in the war, Samuel was tried for his loyalty but, probably because of his high standing in the community, the charges were dismissed. He was later confined to his farm and the order was given that any citizen could shoot him if he was found outside its limits.

His son Oliver, my fourth great grandfather, fled the country and was among a long list of Loyalists who — according to a statute passed in February 1779 — would suffer twenty to forty lashes on their backs if they returned to Vermont, and death if they returned and stayed for more than a month. Fortunately, the law was repealed in November 1780.

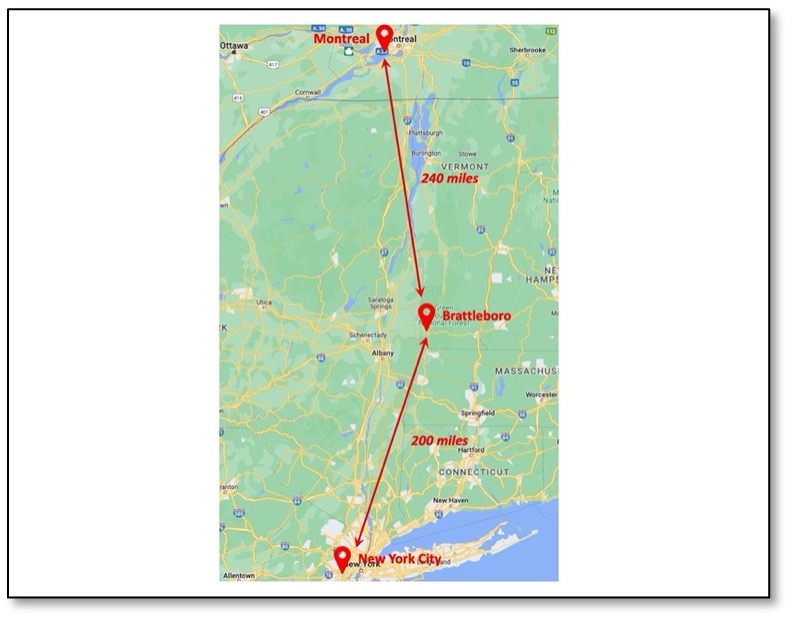

Between 1781 and 1783, Samuel Wells was ideally located to organize a conduit for communications between the British authorities in Lower Canada and those in New York City. Brattleboro is almost equidistant from Montreal, 240 miles north, and New York, 200 miles south. His job was to arrange for secret couriers to carry letters back and forth.

I’ll quote from two of my sources, talking about Samuel’s role, and how his cover was eventually blown.

The first is from Lorenzo Sabine’s Sketches of Loyalists of the American Revolution and says the following of Samuel …

Implicated with those who aimed to reduce Vermont to a dependency of the Crown, and, possibly, a principal man of the party, he fled the country after measures had been taken to arrest him, by Washington, under a vote of Congress in secret session.

So it was George Washington himself who gave the order to arrest Colonel Samuel Wells.

The second excerpt is from the History of Vermont, by Ira Allen (who, you’ll recall, was a leader of the negotiations with Haldimand in Lower Canada):

In January, 1783, the late Colonel Samuel Wells of Brattleborough, being engaged in transmitting letters from Canada to New York, one of his packets was intercepted, and fell into the hands of some of the officers of the Continental troops. In consequence of which, a captain, with a company from Albany, was dispatched to seize the Colonel, who, on being informed of this circumstance, left his house to take shelter in Canada.

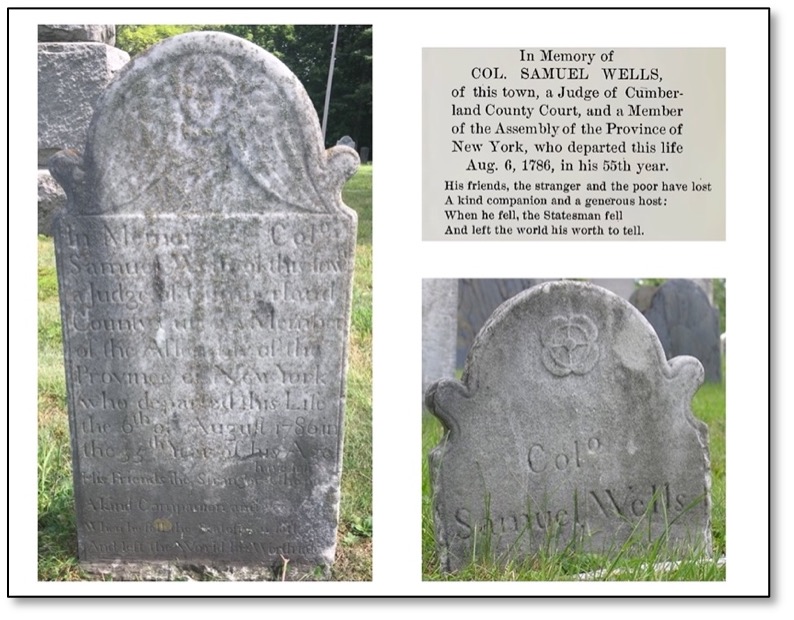

When the war ended, Samuel returned to Brattleboro where, no longer a rich man, he died in poverty in 1786. He was fifty-five. It seems that his high standing in the town had allowed him to avoid imprisonment or death as a traitor, but it wasn’t enough to save him from bankruptcy.

His marble headstone still stands in the cemetery in Brattleboro. The inscription speaks of his public service, his philanthropy, and his statesmanship.

For the next fifteen years, Samuel’s adult children struggled by as best they could. It was in the 1790s that this man, Samuel Gale, began to work on securing their patrimony, based on their father’s Loyalist legacy.

Samuel Gale was a son-in-law of Colonel Wells, having married his daughter Rebecca in 1773. He had been a paymaster in the British army and he moved to Quebec City, in 1791, to become principal assistant to the Surveyor General for Lower Canada.

In his spare time, Gale worked assiduously at lobbying the authorities to grant the Wells family land in the Eastern Townships. There is a fat folder in the national archives, containing transcriptions of more than four years of correspondence between Samuel Gale and whatever senior official would listen to him.

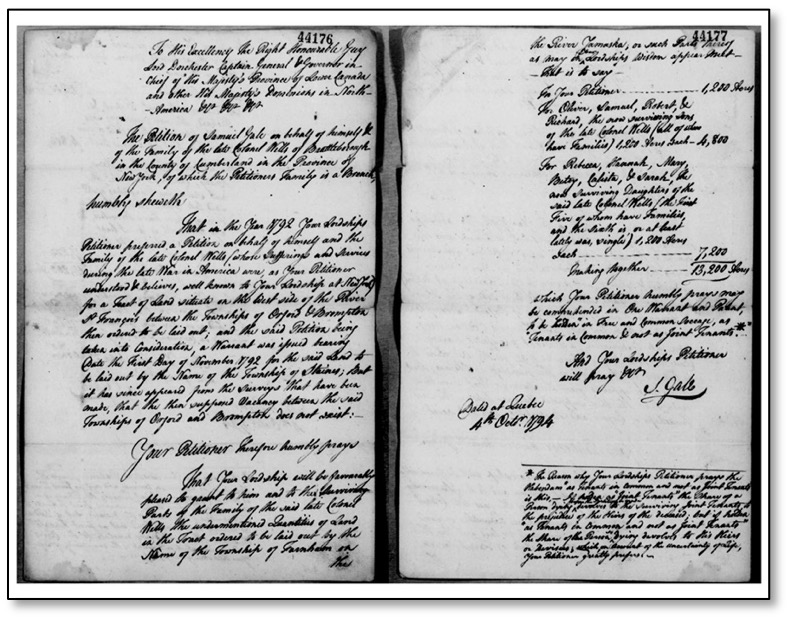

Perhaps the most important is this letter, dated October 4, 1794. It’s from Samuel Gale to Guy Carleton, Lord Dorchester, who was the Governor in Chief of Lower Canada. It was fortuitous that, a dozen years earlier, Lord Dorchester had been commander of the British forces in New York City, and so he had first-hand knowledge of Samuel’s important role.

The letter starts by reminding Dorchester…

[…] of the late Colonel Wells (whose Sufferings and Services during the late War in America were […] well known to Your Lordship at New York).

It later goes on to say that…

Your Petitioner […] humbly prays

That Your Lordship will be favourably pleased to grant to him and to the Surviving Parts of the Family of the said late Colonel Wells the undermentioned Quantities of Land in the Tract ordered to be laid out by the Name of the Township of Farnham on the River Yamaska, or such Parts thereof as may in Your Lordship’s Wisdom appear meet —

The request was approved in principle in 1795, but it was 1798 before the land had been surveyed, the paperwork had been completed, and Samuel’s children and grandchildren were able to travel north.

And that his how the Wells family, the Loyalist branch of my family tree, came to Canada at the turn of the nineteenth century.

Submitted by Descendant Paul Warner UE